Marshal Hubert Lyautey is one of those men who are not remembered by many, but who is never forgotten once we learn about his vision and attitude as a commander:

He was born on November 17th, 1854, in Nancy, France, two months after the battle of Alma.

The story of his formation is one of loyalty and commitment. If these two words mean anything to you, and if you are inspired by the example of the old elites of the recent past, take a moment to discover what his life was like:

Like many of his ancestors, Hubert Lyautey was early destined for a military career and entered the French army high school of Saint-Cyr in 1873. After continuing his training at the war school, he was sent to Algeria, where he remained as a cavalry officer for two years. When he returned to Europe, Lyautey visited the Count of Chambord in exile to show his devotion. But, faced with the division and weakness of the royalists, he had to rally to the Republic, not by conviction but by reason.

He used his talent in a colonial career, at a time when modern methods of governance wanted to wipe out traditions.

Hubert Lyautey was not one of those men who knew the world through maps and countries through travelers’ accounts. He could tell you the names of the streets of the capitals, describe the taste of the local dishes, and speak of the character of the inhabitants.

An exceptional character gifted with remarkable intelligence in action, Hubert Lyautey devoted several works to the military profession. The essay he published in 1891 in La Revue des Deux Mondes, “Du rôle social de l’officier dans le service militaire universel” (The social role of the officer in universal military service), in which he made known his humanist conception of the army, had a great impact and influenced a whole generation of officers. He developed these themes in a work entitled “The Social Role of the Army” (1900).

His colonial career began with Tonkin (North Viet Nam) in 1894, then Madagascar in 1897.

As a colonel in 1900, Lyautey succeeded in pacifying this region and promoting its economic development. These two actions define the vision and the imprint he will leave in the country that was to become his second home: Morocco.

In 1903, he was called to Algeria, then a colony of France. He worked effectively to maintain peace and received his general’s stars.

Finally, in 1912, the man nicknamed “Lyautey the African” became the first resident general of France in Morocco.

There he showed the full measure of his genius as a strategist and great administrator. He made perfect use of his deep knowledge of the region, the terrain, and the customs of the tribes.

His great respect for the local traditions and the person of the Sultan was his primary strategy to make himself respected in return by the tribal chiefs and religious leaders.

Commander of the believers. He won the local elites’ trust by showing his consideration for their culture without ever giving up his own.

Indeed, Lyautey, from a Catholic tradition, never chose to denigrate his own identity, as do the modern “elites,” who believe that the absence of an identity of their own facilitates communication and exchanges.

He demonstrated that it is, on the contrary, the affirmation of what one is that makes mutual understanding possible.

And the imprint he left in people’s memories would decide the rest

He knew how to soothe, and he also knew how to build, creating in particular Casablanca, the first structure of modern Morocco.

To speak of Lyautey, Hassan 2 said of him, “The colonizer fell in love with the colonized and the colonized with the colonizer.”

During the First World War, he temporarily left his functions to become Minister of War for 11 weeks, between December 1916 and March 1917.

After returning to Morocco, he was made Marshal of France in 1921.

However, due to the purely ideological hostility of the cartel of the left, during the presidency of Raymond Poincaré (the brother of Henri Poincaré, the first discoverer of the formula E=mc2), he was deprived of the command of the troops engaged against Abd-el-Krim’s rebellion and entrusted them to Pétain.

While Lyautey was on the verge of winning the Rif war thanks to alliance games between the tribes, Philippe Pétain refused this winning strategy and preferred the catastrophic strategy of bombing.

Lyautey, aware of the historical mistake that this represented, resigned and returned to France in 1925. Before his death, he fulfilled one last mission: the organization of the 1931 Colonial Exhibition.

The secret of Lyautey’s vision has a name: Ethnodifferentialism.

This term refers to a philosophical conception of relations between Europe and the rest of the world based on respect for identities. “Africans are not inferior; they are other,” he wrote in the 1920s.

This sentence alone is enough to show how his vision contrasts with the supposedly egalitarian doctrine of modern “humanists.”

His conception remained marginal in France and Europe. It contradicts that of Jules Ferry, Léon Blum, or the current thinkers of the moral left. They, each in their way, cultivate the conviction that the rich Westerners must “help” the “underdeveloped” peoples (which in reality means inferior in their unconscious) to follow in their footsteps.

It is only by studying Lyautey that one understands the profound difference in worldview between the ancient elites and the modern ones.

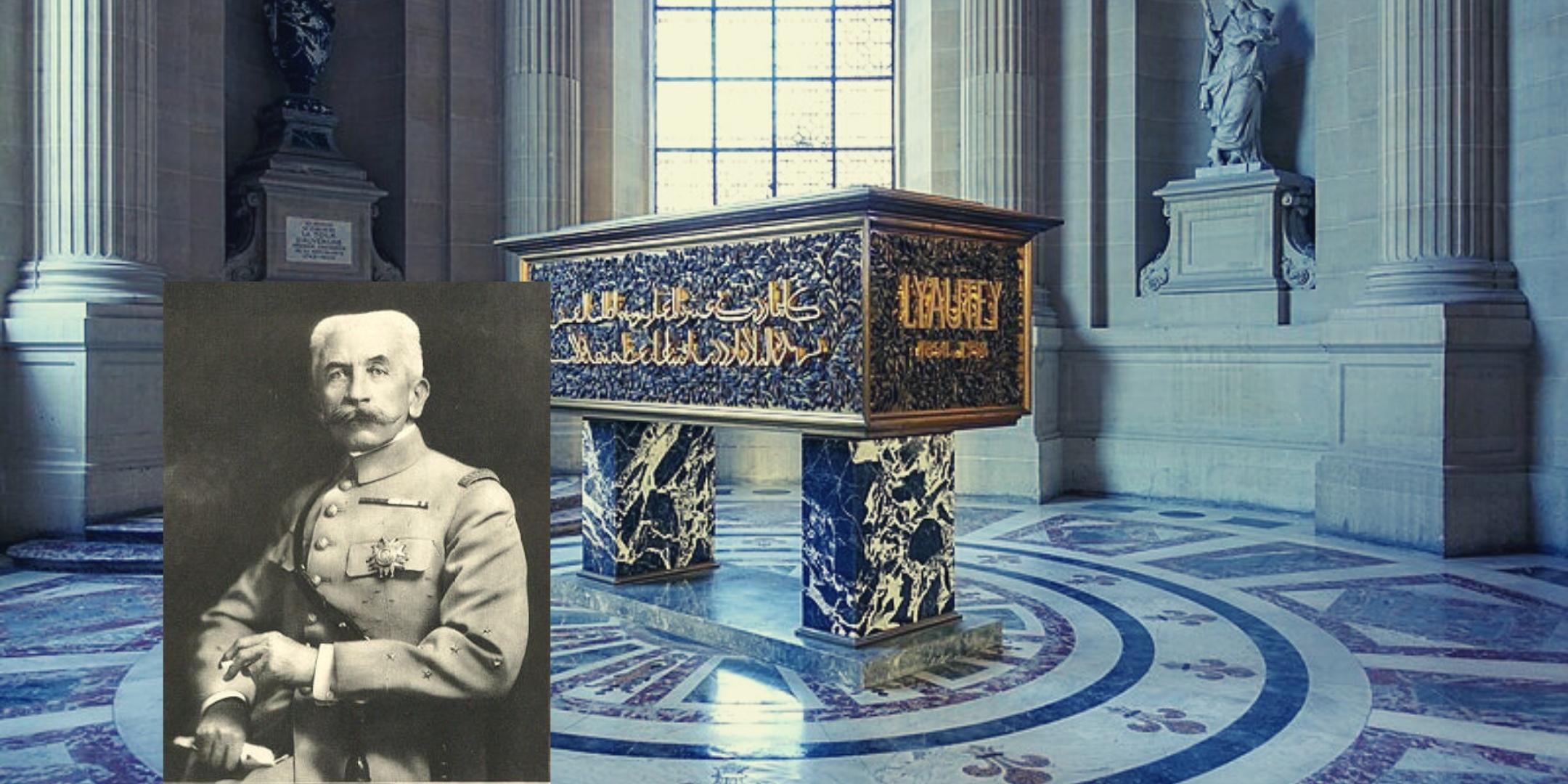

Lyautey died in France on July 27th, 1934, and was buried in Rabat. In 1961, his remains were returned to France to be deposited at the Invalides.

After the mass, the coffin of Marshal Lyautey, escorted by a detachment of Moroccan Saint-Cyriens and Spahis, was carried to the bronze and copper coffin, decorated with oak leaves, where are engraved in French and Arabic these words of the former resident general of France in Morocco:

“To be one of those in whom men believe, in whose eyes millions of eyes seek order, at whose voice roads open, countries are populated and cities arise. “

In a certain sense, we can say that his legacy, which is one of his visions of peoples and civilizations, has been buried by modernity.

It, therefore, exists only for those who have made an effort to discover his work and the philosophy he tried to embody.

In anthropology, it is sometimes said that every pivotal era is the tomb of a bygone era and the cradle of an age yet to be discovered. It is precisely in this era that Hubert Lyautey left his mark.